Of two minds

De bonnes raisons de se mettre aux langues étrangères… vu par “The Economist”, in English please!

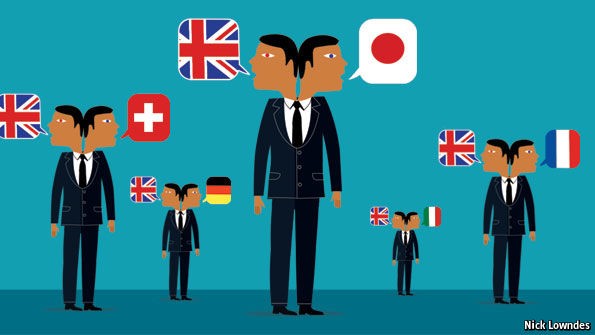

The advantages of working in your own language are obvious. Those of working in a foreign one are subtle.

MORE and more of the world is working in English. Multinational companies (even those based in places such as Switzerland or Japan) are making it their corporate language. And international bodies like the European Union and the United Nations are doing an ever-greater share of business in the world’s new default language. At the office, it’s English’s world, and every other language is just living in it.

Is this to the English-speaker’s advantage?

Working in a foreign language is certainly hard. It is easier to argue fluently or to make a point subtly when not trying to call up rarely used vocabulary or construct sentences correctly. English-speakers can try to bulldoze opposing arguments through sheer verbiage, hold the floor to prevent anyone else from getting a word in or lighten the mood with a joke. All of these things are far harder in a foreign language. Non-natives have not one hand, but perhaps a bit of their brains, tied behind their backs. A recent column by Michael Skapinker in the Financial Times says that it’s important for native English-speakers to learn the skills of talking with non-natives successfully.

But, as Mr Skapinker notes, there are advantages to being a non-native, too. These are subtler—but far from trivial. Non-native speakers may not be able to show off their brilliance easily. It can be an advantage to have your cleverness highly rated, and this is the luck of verbally fluent people around the world. But it is quite often the other way round: it can be a boon to be thought a little dimmer than you really are, giving the element of surprise in a negotiation. And, as an American professor in France tells Johnson, coming from another culture—not just another language—allows people to notice stumbling blocks and habits of thinking shared by the rest of the natives, and guide a meeting past them. Such heterodox thinking can be wrapped in a bit of disingenuous cluelessness: “I’m not sure how things work here, but I was thinking…”

People working in a language not their own report other perks. Asking for a clarification can buy valuable time or be a useful distraction, says a Russian working at The Economist. Speaking slowly allows a non-native to choose just the right word—something most people don’t do when they are excited and emotional. There is a lot to be said for thinking faster than you can speak, rather than the other way round.

Most intriguingly, there may be a feedback loop from speech back into thought. Ingenious researchers have found that sometimes decision-making in a foreign language is actually better. Researchers at the University of Chicago gave subjects a test with certain traps—easy-looking “right” answers that turned out to be wrong. Those taking it in a second language were more likely to avoid the trap and choose the right answer. Fluid thinking, in other words, has its down-side, and deliberateness an advantage. And one of the same researchers found that even in moral decision-making—such as whether it would be acceptable to kill someone with your own hands to save a larger number of lives—people thought in a more utilitarian, less emotional way when tested in a foreign language. An American working in Denmark says he insisted on having salary negotiations in Danish—asking for more in English was excruciating to him.

All this applies regardless of the first language. But in the modern world it is English monoglots in particular who work in their own language, joined by non-native polyglots working in English too. Those non-native speakers can always go away and speak their languages privately before rejoining the English conversation. Hopping from language to language is a constant reminder of how others might see things differently, notes a Dutch official at the European Commission. (One study found that bilingual children were better at guessing what was in other people’s heads, perhaps because they were constantly monitoring who in their world spoke what language.) It was said that Ginger Rogers had to do every step Fred Astaire did, but “backwards, and in high heels”. This, unsurprisingly, made her an outstanding dancer.

Indeed, those working in foreign languages are keen to talk about these advantages and disadvantages. Alas, monoglots will never have that chance. Pity those struggling in a second language—but also spare a thought for those many monoglots who have no way of knowing what they are missing.

Apr 7th 2016 Article original sur THE ECONOMIST